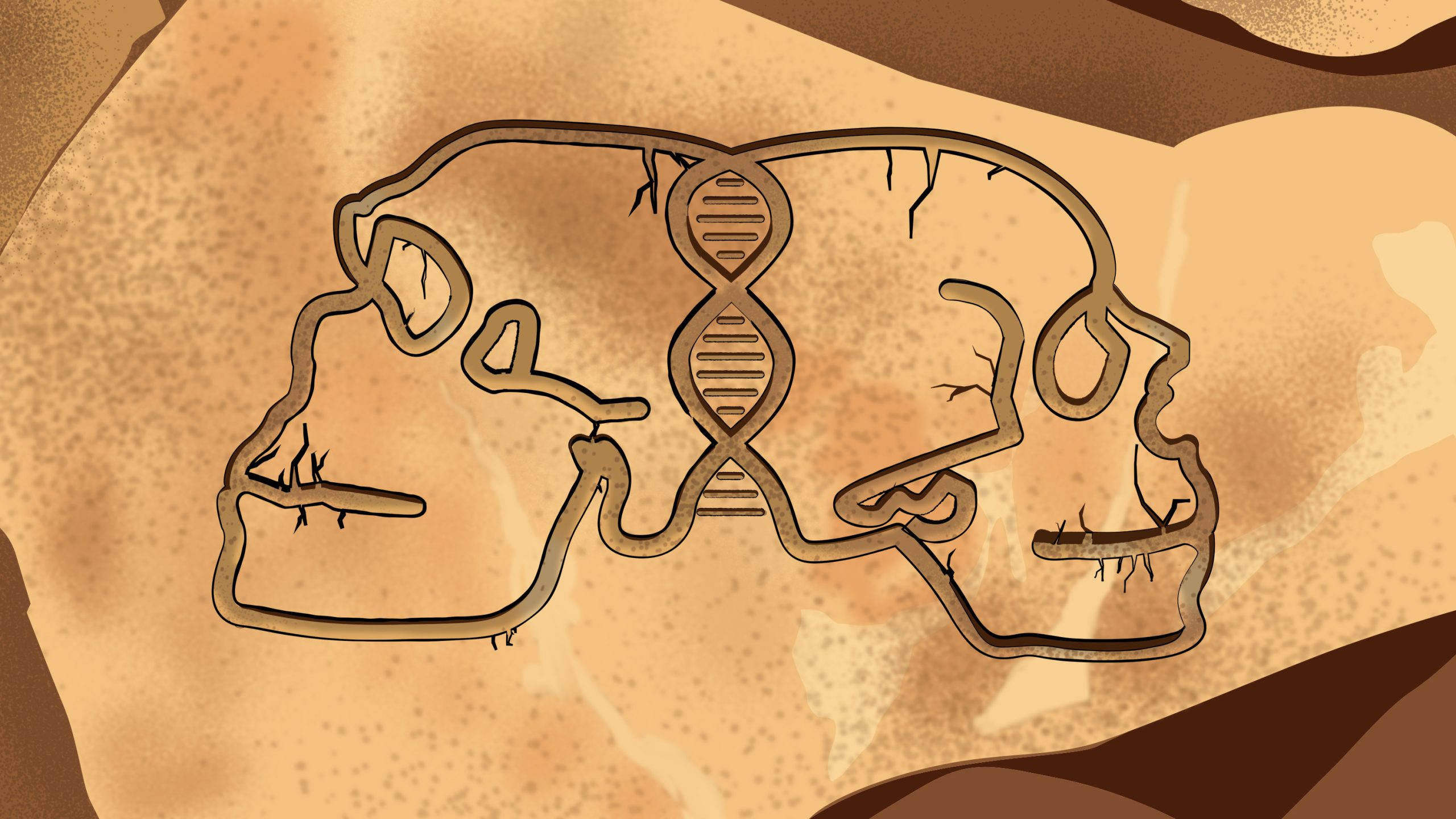

An international team led by Josh Akey of Princeton University and Liming Li of Southeast University reported that modern humans have been interbreeding with Neanderthals for more than 200,000 years. Akey and Li identified a first wave of contact around 200-250,000 years ago, another wave around 100-120,000 years ago, and the largest wave around 50-60,000 years ago. They used a genetic tool called IBDmix that uses artificial intelligence, rather than a reference group of living humans, to analyze 2,000 living humans, three Neanderthals, and one Denisovan. Copyright: Matilda Locke, Princeton University

Geneticist Joshua Akey says modern humans and Neanderthals interacted for 200,000 years.

New genetic research reveals extensive interbreeding and long-term interactions between Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans, suggesting a more integrated history than previously understood and supporting theories of Neanderthal assimilation into modern human populations.

Since the first Neanderthal bones were discovered in 1856, curiosity about these ancient humans has grown. What makes them different from us? How similar are they to us? Did our ancestors get along with them? Did they fight them? Or did they love them? The recent discovery of a group called Denisovans, a Neanderthal-like population that inhabited Asia and South Asia, has added another set of questions.

Now, an international team of geneticists and AI experts is adding entirely new chapters to our shared human history. Led by Joshua Akey, a professor at the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University, the researchers have uncovered a history of mixing and genetic exchange that suggests these early human groups were more closely related than previously thought.

“This is the first time that geneticists have identified multiple waves of admixture between modern humans and Neanderthals,” said Liming Li, a professor in the Department of Medical Genetics and Developmental Biology at Southeast University in Nanjing, China, who conducted the work as a research associate in Akey’s lab.

“We now know that for the vast majority of human history, we had a history of contact between modern humans and Neanderthals,” Akey said. The hominins who are our most direct ancestors split off from the Neanderthal family tree about 600,000 years ago, and then evolved our modern physical characteristics about 250,000 years ago.

Continuous interaction over thousands of years

“From then until the disappearance of Neanderthals – about 200,000 years ago – modern humans interacted with Neanderthal groups,” he said.

The results of their work appear in the current issue of the journal. Sciences.

Once seen as slow-moving and stupid, Neanderthals are now seen as skilled hunters and toolmakers who treated others’ injuries with sophisticated techniques and were well adapted to thrive in the cold European climate.

(Note: All of these hominin groups are humans, but to avoid saying “Neanderthals,” “Denisovans,” and “early versions of our own species,” most archaeologists and anthropologists use the abbreviation “Neanderthals,” “Denisovans,” and “modern humans.”)

Using the genomes of 2,000 living humans, as well as three Neanderthals and one Denisovan, Akey and his team mapped gene flow between hominin groups over the past quarter million years. The researchers used a genetic tool they designed few years There was a program called IBDmix, which used machine learning techniques to decode the genome. Previous researchers had relied on comparing human genomes to a “reference group” of modern humans thought to have little or no Neanderthal or Denisovan genes. DNA.

Akey’s team has shown that even these groups, living thousands of miles south of the Neanderthal caves, have trace amounts of Neanderthal DNA, which may have been carried south by the travelers (or their descendants). Using IBDmix, Akey’s team identified a first wave of contact around 200-250 thousand years ago, another wave around 100-120 thousand years ago, and the largest wave around 50-60 thousand years ago.

Review of human migration models

This is in sharp contrast to previous genetic data. “Until now, most genetic data suggests that modern humans evolved in Africa 250,000 years ago, stayed there for another 200,000 years, and then moved into Africa in the 1950s. then “Ancient humans decided to spread out of Africa 50,000 years ago and spread to the rest of the world,” Aki said.

“Our models show that there was not a long period of stagnation, but that shortly after modern humans emerged, we started migrating out of Africa and back into Africa as well,” he said. “To me, this story is about dispersal, where modern humans were moving around and encountering Neanderthals and Denisovans much more than we previously realized.”

This vision of mobile humanity is consistent with early archaeological and anthropological research that points to cultural and tool exchange between hominin groups.

The main idea that Lee and Aki came up with was to look for modern human DNA in Neanderthal genomes, rather than the other way around. “The vast majority of genetic work over the past decade has focused on how interbreeding with Neanderthals has affected modern human phenotype and our evolutionary history—but these questions are relevant and interesting in reverse, too,” Aki says.

They realized that the offspring of those first waves of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans must have stayed with Neanderthals, leaving no trace among living humans. “Because we can now incorporate the Neanderthal component into our genetic studies, we see these early dispersals in ways we couldn’t before,” Akey says. The final piece of the puzzle was the discovery that the Neanderthal population was smaller than previously thought.

Genetic modeling has traditionally used variance—diversity—as a measure of population size. The more diverse the genes, the larger the population. But using IBDmix, Akey’s team showed that much of this phenotypic diversity came from DNA sequences taken from modern humans, whose population was much larger.

As a result, the actual population of Neanderthals was reduced from about 3,400 reproductive individuals to about 2,400.

Overall, the new findings paint a picture of how Neanderthals disappeared from the record, some 30,000 years ago.

“I don’t like to say ‘extinction,’ because I think Neanderthals are pretty much extinct,” Akey says. His idea is that Neanderthal numbers slowly declined until the last survivors integrated into modern human societies.

Fred Smith, a professor of anthropology at Illinois State University, was the first to formulate this “assimilation model” in 1989. “Our results provide strong genetic data consistent with Fred’s hypothesis, and I think that’s really exciting,” Akey says.

“Neanderthals were on the verge of extinction, and probably had been for a very long time. If we reduce their numbers by 10 or 20 percent, which is what our estimates suggest, that would mean a significant reduction in an already vulnerable population,” he said.

“Modern humans were basically like waves crashing on a beach, slowly but surely eroding the beach. Eventually, we were able to demographically outcompete the Neanderthals and integrate them into modern human populations.”

Reference: “Repeated Gene Flow between Neanderthals and Modern Humans over the Past 200,000 Years” by Liming Li, Troy J. Comey, Robert F. Berman, and Joshua M. Akey, July 12, 2024, Sciences.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1768

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (Grant R01GM110068 to JMA).

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin