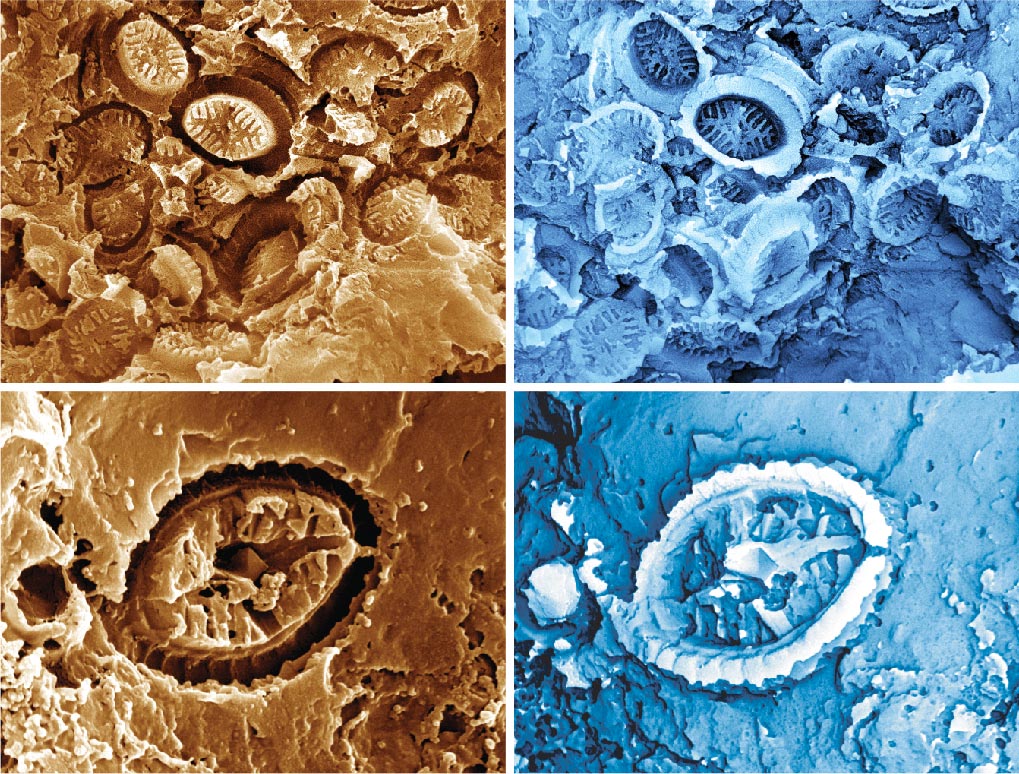

Images show impressions of a collapsed cell wall covering (cocosphere) on the surface of a fragment of ancient organic matter (left) with individual plates magnified (coccyx) to show the remarkable preservation of sub-micron-scale structures (right). The blue image is inverted to give a virtual fossil image, that is, to show the original 3D shape. The original slabs were removed from the sediment by dissolution, leaving behind only traces of ghosts. Credit: S.M. Slater, P. Bowen/Science Journal

An international team of researchers has discovered a new type of fossilization.

The discovery of ‘ghost’ fossils reveals the resilience of plankton in the face of past global warming events.

An international team of scientists from University College London (UCL), the Swedish Museum of Natural History, the Natural History Museum (London), and the University of Florence has found a remarkable type of fossilization that has remained virtually unnoticed until now.

Fossils are microscopic fingerprints, or “ghosts,” of single-celled plankton, called coccolithophores, that lived in seas millions of years ago, and their discovery revolutionized our understanding of how climate change affects plankton in the oceans.

Coccolithophores are important in today’s oceans, providing much of the oxygen we breathe, supporting marine food webs, and trapping carbon away in seafloor sediments. They are a type of microscopic plankton that surround their cells with hard limestone slabs, called coccoliths, which are what usually decompose in rocks.

The decrease in the abundance of these fossils has been documented from several pre-global warming events, indicating that these plankton have been severely affected by climate change and ocean acidification. However, a study was published today in the journal Science Presents new world records for the abundant ghost fossils of three[{” attribute=””>Jurassic and Cretaceous warming events (94, 120, and 183 million years ago), suggesting that coccolithophores were more resilient to past climate change than was previously thought.

The individual plates are coccoliths. Credit: Images from Nannotax https://www.mikrotax.org/Nannotax3/

“The discovery of these beautiful ghost fossils was completely unexpected,” says Dr. Sam Slater from the Swedish Museum of Natural History. “We initially found them preserved on the surfaces of fossilized pollen, and it quickly became apparent that they were abundant during intervals where normal coccolithophore fossils were rare or absent – this was a total surprise!”

Despite their microscopic size, coccolithophores can be hugely abundant in the present ocean, being visible from space as cloud-like blooms. After death, their calcareous exoskeletons sink to the seafloor, accumulating in vast numbers, and forming rocks such as chalk.

The fossils are approximately 5 µm in length, 15 times narrower than the width of a human hair. Credit: S.M. Slater, P. Bown et al. / Science journal

“The preservation of these ghost nannofossils is truly remarkable,” says Professor Paul Bown (UCL). “The ghost fossils are extremely small ‒ their length is approximately five-thousandths of a millimeter, 15 times narrower than the width of a human hair! ‒ but the detail of the original plates is still perfectly visible, pressed into the surfaces of ancient organic matter, even though the plates themselves have dissolved away.”

The ghost fossils formed while the sediments at the seafloor were being buried and turned into rock. As more mud was gradually deposited on top, the resulting pressure squashed the coccolith plates and other organic remains together, and the hard coccoliths were pressed into the surfaces of pollen, spores, and other soft organic matter. Later, acidic waters within spaces in the rock dissolved away the coccoliths, leaving behind just their impressions – the ghosts.

Ghost nannofossils were found in rocks from global warming intervals where normal coccolithophore fossils were rare or absent. Credit: S.M. Slater, P. Bown, et al. / Science journal

“Normally, paleontologists only search for the fossil coccoliths themselves, and if they don’t find any then they often assume that these ancient plankton communities collapsed,” explains Professor Vivi Vajda (Swedish Museum of Natural History). “These ghost fossils show us that sometimes the fossil record plays tricks on us and there are other ways that these calcareous nannoplankton may be preserved, which need to be taken into account when trying to understand responses to past climate change.”

Professor Silvia Danise (University of Florence) says: “Ghost nannofossils are likely common in the fossil record, but they have been overlooked due to their tiny size and cryptic mode of preservation. We think that this peculiar type of fossilization will be useful in the future, particularly when studying geological intervals where the original coccoliths are missing from the fossil record.”

Ghost nannofossils were found globally, in rocks from three rapid warming events in Earth’s history (the T-OAE, OAE1a, and OAE2). Credit: S.M. Slater et al.

The study focused on the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE), an interval of rapid global warming in the Early Jurassic (183 million years ago), caused by an increase in CO2-levels in the atmosphere from massive volcanism in the Southern Hemisphere. The researchers found ghost nannofossils associated with the T-OAE from the UK, Germany, Japan, and New Zealand, but also from two similar global warming events in the Cretaceous: Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a (120 million years ago) from Sweden, and Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 (94 million years ago) from Italy.

“The ghost fossils show that nannoplankton were abundant, diverse, and thriving during past warming events in the Jurassic and Cretaceous, where previous records have assumed that plankton collapsed due to ocean acidification,” explains Professor Richard Twitchett (Natural History Museum, London). “These fossils are rewriting our understanding of how the calcareous nannoplankton respond to warming events.”

Finally, Dr. Sam Slater explains: “Our study shows that algal plankton were abundant during these past warming events and contributed to the expansion of marine dead zones, where seafloor oxygen-levels were too low for most species to survive. These conditions, with plankton blooms and dead zones, may become more widespread across our globally warming oceans.”

Reference: “Global record of “ghost” nannofossils reveals plankton resilience to high CO2 and warming” by Sam M. Slater, Paul Bown, Richard J. Twitchett, Silvia Danise and Vivi Vajda, 19 May 2022, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abm7330

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin