Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe With news of amazing discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

–

A scan of a 319-million-year-old fossilized skull fish It led to the discovery of the oldest example of a well-preserved vertebrate brain, shedding new light on the early evolution of bony fishes.

The fossil skull belonging to the extinct Coccocephalus wildi was found in a coal mine in England more than a century ago, according to researchers from study Published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

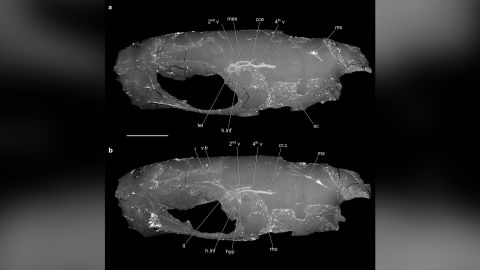

The fossil is the only known specimen of a fish species, so scientists from the University of Michigan in the US and the University of Birmingham in the UK used non-destructive computed tomography (CT) scanning technology to look inside its skull and examine the inside. somatic structure.

Upon doing so, a surprise came. The CT image showed an “unidentified point,” a University of Michigan press release said.

The distinct three-dimensional object had a clearly defined structure with features found in vertebrate brains: it was bilaterally symmetrical, contained hollow spaces similar in appearance to ventricles and had extended filaments resembling cranial nerves.

“This is an exciting and unexpected finding,” study co-author Sam Giles, a vertebrate paleontologist and senior research scientist at the University of Birmingham, told CNN on Thursday, adding that they had “no idea” there was a brain inside when they decided to study the skull.

“It was so unexpected that it took us a while to confirm that it was, in fact, a brain. Aside from being just a precautionary curiosity, the anatomy of the brain in this fossil has major implications for our understanding of brain development in fish.”

C. wildi was an early ray-finned fish—which had a backbone and fins supported by bony rods called “rays”—that is thought to have been 6 to 8 inches long, swam in estuaries, and ate small aquatic animals and aquatic insects according to the researchers.

The brains of living ray-finned fish display structural features not seen in other vertebrates, most notably the forebrain, which consists of nervous tissue that folds outward, according to the study. In other vertebrates, this nerve tissue folds inwards.

C. wildi lacks this characteristic of ray-finned fish, with a configuration of a part of the forebrain called the “distal brain” that is very similar to other vertebrates, such as amphibians, birds, reptiles and mammals, according to the study authors.

“This suggests that distal brain formation seen in living ray-finned fish must have emerged much later than previously thought,” said lead study author Rodrigo Tinoco Figueroa, a doctoral student at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology.

He added that “our knowledge of vertebrate brain evolution is mostly limited to what we know from living organisms,” but “this fossil helps us fill important gaps in knowledge, which can only be gleaned from exceptional fossils like this one.”

Unlike hard bones and teeth, scientists rarely find brain tissue — which is soft — preserved in vertebrate fossils, according to the researchers.

However, the study noted that C. wildi’s brain was “exceptionally” healthy. While invertebrate brains up to 500 million years old have been found, they are all flattened, Giles said, adding that this vertebrate brain is “the oldest three-dimensional fossil brain of anything we know of.”

The skull was found in layers of soapstone. Low oxygen concentration, rapid burial by fine-grained sediment, and a highly compact and protective conical cranium all play key roles in preserving the fish’s brain, according to Figueroa.

The cerebrum created a delicate chemical environment around the closed brain that would have helped replace its soft tissues with a dense mineral that preserves the fine detail of the three-dimensional brain structures.

“The next steps are to find out exactly how such delicate features as the brain could have been preserved for hundreds of millions of years, and to look for more brain-preserving fossils,” Giles said.

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin