Research suggests that the unusual state of the Earth’s magnetic field during the Ediacaran period could have had a significant impact on the evolution of complex life by modifying oxygen levels in the atmosphere. The study reveals that this period saw the weakest magnetic field ever, which may have allowed more oxygen, thus supporting larger and more active life forms. This enhanced understanding of geomagnetic and evolutionary dynamics provides insight into the potential for life on other planets. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Evidence suggests that a weak magnetic field millions of years ago may have given rise to life.

The Ediacara Period, which extended from about 635 to 541 million years ago, was a pivotal period in Earth’s history. It was a transformative era during which complex, multicellular organisms emerged, paving the way for the explosion of life.

But how did this surge in life develop and what factors on Earth might have contributed to it?

Researchers from the University of Rochester have discovered compelling evidence that the Earth’s magnetic field was in a highly unusual state when macroscopic fauna diversified and flourished in the Ediacaran period. Their study was published in nature Communications Earth and environmentThis raises the question of whether these fluctuations in Earth’s ancient magnetic field led to changes in oxygen levels that may have been crucial to the reproduction of life forms millions of years ago.

Researchers from the University of Rochester studied Earth’s magnetic field during the Ediacaran Transitional Period, which spanned from about 635 to 541 million years ago. The research raises questions about what factors may have fueled the emergence of complex, multicellular organisms, such as Ediacaran animals, known for their similarity to early animals. Credit: University of Rochester illustration/Michael Osadcio

According to John Tarduno, the William Kennan Jr. Professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, one of the most prominent life forms during the Ediacaran period were the Ediacaran animals. They were notable for their similarity to early animals, some of which were more than a meter (three feet) in size and were mobile, suggesting they may have needed more oxygen than previous life forms.

“Previous ideas about the emergence of these amazing Ediacaran animals have included genetic or environmental driving factors, but the close timing with the extremely low magnetic field has prompted us to reconsider environmental issues, in particular, oxygen in the atmosphere and oceans,” says Tarduno. He is also the Dean of Research in the College of Arts and Sciences and the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Earth’s magnetic secrets

About 1,800 miles below us, liquid iron flows into Earth’s outer core, creating the planet’s protective magnetic field. Although the magnetic field is invisible, it is essential for life on Earth because it protects the planet from the solar wind – streams of radiation coming from the Sun. But the Earth’s magnetic field was not always as strong as it is today.

The researchers suggested that an unusually low magnetic field may have contributed to the emergence of animal life. However, the correlation has been difficult to examine due to limited data on magnetic field strength during this time.

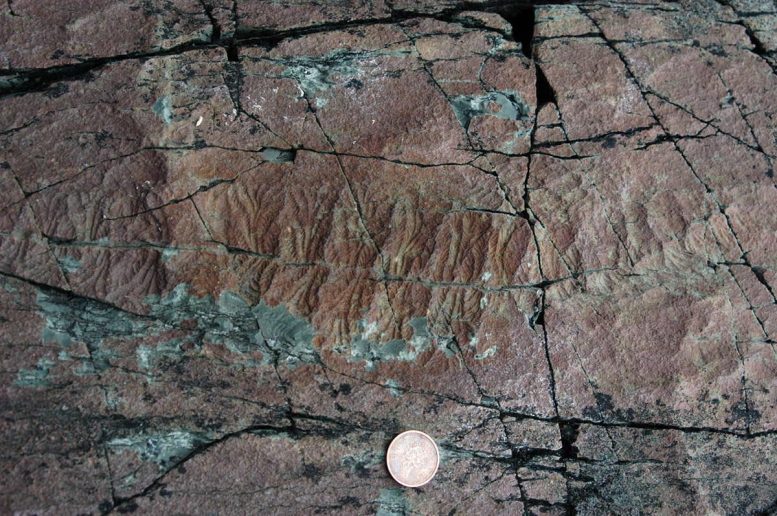

A fossil impression of Dickinsonia, an example of an Ediacaran fauna, found in present-day Australia. Credit: Shuhai Xiao, Virginia Tech

Tarduno and his team used innovative strategies and techniques to examine the strength of the magnetic field by studying the magnetism found in ancient feldspar and pyroxene crystals from the anorthosite rock. Crystals contain magnetic particles that maintain magnetization since the formation of minerals. By dating rocks, researchers can create a timeline for the evolution of Earth’s magnetic field.

Take advantage of advanced tools, including CO2 Using lasers and a Superconducting Quantum Interferometer (SQUID) magnetometer in the lab, the team carefully analyzed the crystals and the magnetism within them.

Weak magnetic field

Their data indicate that the Earth’s magnetic field at times during the Ediacaran period was the weakest field known to date—up to 30 times weaker than today’s magnetic field—and that the extremely low field strength persisted for at least 26 million years.

The weak magnetic field on charged particles from the Sun makes it easier for lightweight atoms like hydrogen to be stripped from the atmosphere, causing them to escape into space. If the loss of hydrogen is large, more oxygen may remain in the atmosphere rather than react with the hydrogen to form water vapor. These reactions can lead to oxygen buildup over time.

A fossil impression of Fractofusus, an example of an Ediacaran fauna, was found in what is now known as Newfoundland, with a Canada penny close in size. Credit: Shuhai Xiao, Virginia Tech

Research by Tarduno and his team suggests that during the Ediacaran period, an extremely weak magnetic field caused hydrogen loss over at least tens of millions of years. This loss may have increased oxygen in the atmosphere and ocean surface, enabling more advanced life forms to emerge.

Tarduno and his research team previously discovered that the Earth’s magnetic field regained strength during the later Cambrian, when most animal groups began to appear in the fossil record, and the protective magnetic field was re-established, allowing life to flourish.

“If the very weak field had remained after the Ediacaran, the Earth would have looked very different from the water-rich planet it does today: the loss of water might have gradually dried out the Earth,” says Tarduno.

Basic dynamics and evolution

The work suggests that understanding the interior design of planets is crucial in thinking about the potential for life beyond Earth.

“It’s amazing to think that processes occurring in the Earth’s core can ultimately be linked to evolution,” Tarduno says. “As we consider the possibility of life elsewhere, we also need to consider how the interiors of planets form and evolve.”

For more information about this research, see How Earth’s weak magnetic field fueled the emergence of complex life.

Reference: “Imminent collapse of the geomagnetic field may have contributed to atmospheric oxygenation and animal radiation in the Ediacaran” by Wentao Huang, John A. Eric J. Blackman, and Alexei V. Smirnoff, Gabriel Ahrendt, and Rory D. Cottrell, and Kenneth B. Kodama, and Richard K. Bono, and David J. Sepik, Yongxiang Li, Francis Nimmo, Shuhai Xiao, and Michael K. Watkes, May 2, 2024, Earth and Environment Communications.

doi: 10.1038/s43247-024-01360-4

This research was supported by the US National Science Foundation.

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin