Researchers studying the effects of a massive black hole collision may have confirmed the gravitational phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein a century ago.

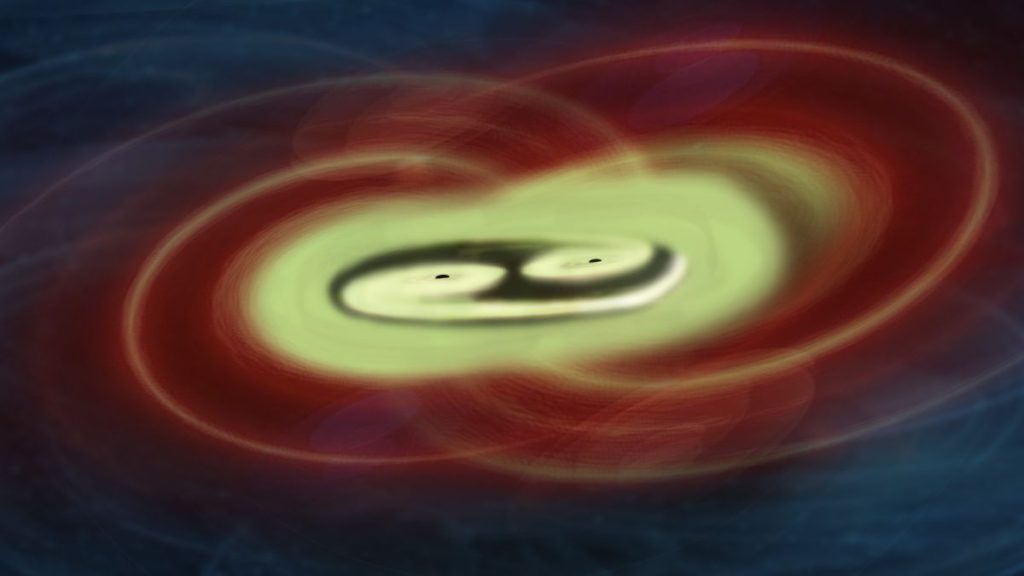

according to New research posted today (Opens in a new tab) (October 12) in Nature, the phenomenon — known as precipitation and similar to the wobbly motion sometimes seen in a spinning top — occurred when two ancient spikes occurred black holes They smashed together and merged into one. As the two massive objects came close together, they released massive ripples through the fabric of spacetime known as gravitational waves, which blasted outward through the universe, carrying energy and angular momentum away from the merging black holes.

Scientists first detected these waves emitted from black holes in 2020 using Gravitational Wave Laser Interferometer (LIGO) in the United States and gravitational wave sensors from Virgo in Italy. Now, after years of studying wave patterns, researchers have confirmed that one of the black holes was spinning like crazy, to a degree never seen before.

Related: How do dancing black holes get close enough to merge

The spinning black hole was twisted and spinning 10 billion times faster than any previously observed, distorting space and time so much that it caused black holes to wobble — or wobble — in their orbits.

The researchers observed a proactive presence in everything from spindle tops to Dying star systems, but never in massive objects like binary black hole systems, where the cosmic broom revolves around a common center. However, Einstein General theory of relativity He predicted more than 100 years ago that precession should happen in things as large as binary black holes. Now, the study authors say, this rare phenomenon has been observed in nature for the first time.

Related: Researchers discover the first merger of black holes with eccentric orbits

“We’ve always thought that binary black holes can do just that,” said senior study author Mark Hannam, director of the Gravity Exploration Institute at Cardiff University in the UK. statement (Opens in a new tab). “We’ve been hoping for an example since the first gravitational wave discoveries. We’ve had to wait five years and over 80 separate discoveries, but we finally have one!”

The black holes in question were several times larger than the black holes the sunThe greater of the two is estimated to be about 40 solar masses. Researchers first detected the winds of the binary pair in 2020, when LIGO and Virgo detected an explosion of gravitational waves from the supposed collision of two black holes. The team named this collision GW200129, for the date of its discovery (January 29, 2020).

Since then, other scientists have pored over initial gravitational-wave data, revealing strange secrets about this epic collision. (Although scientists have only gravitational waves to go on and no direct observations, they can’t pinpoint the exact location of black holes.)

For example, in May 2022, a team of researchers calculated that merging between black holes was both bulky and unbalancedwith gravitational waves emitted from the collision in one direction while the newly merged black hole is likely to be “ejected” from its parent galaxy at over 3 million miles per hour (4.8 million km/h) in the opposite direction.

This new research in the journal Nature suggests that the two black holes had a chaotic relationship before their violent merger. As the two giant bodies dragged each other into an orbit ever closer, they began swaying like puffy tops, advancing several times every second. According to the study authors, this pre-effect is estimated to be 10 billion times faster than any other effect ever measured.

These results validate Einstein, who predicted that such effects were possible in some of the large objects in the universe. But the findings also raise the question of whether wobbly black hole mergers like this are as rare as previously thought.

“The largest black hole in this binary, which was about 40 times larger than the Sun, was spinning as fast as physically possible,” said study co-author Charlie Hoy, a researcher at Cardiff University at the time of the study. Now at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, “Our current models of how binaries form suggest that this model was very rare, perhaps one in a thousand. Or it could be a sign that our models need to change.”

Originally published on Live Science.

Follow us on Twitter Tweet embed (Opens in a new tab) or on Facebook (Opens in a new tab).

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin