BUSAN, South Korea — NASA has canceled a robotic lunar rover mission that was set to search for ice at the moon’s south pole, citing development delays and cost overruns.

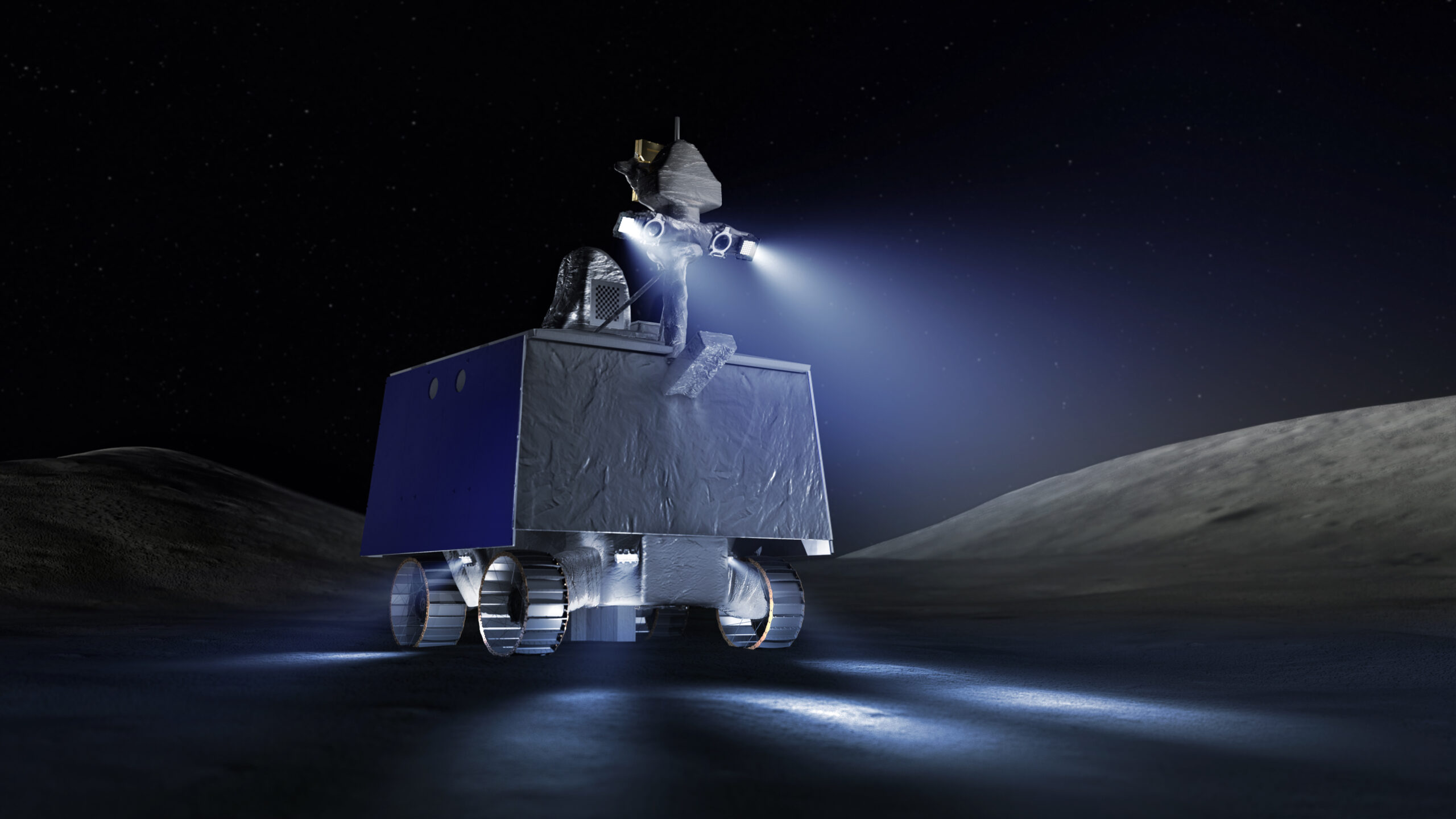

NASA announced on July 17 that it was ending development of the Volatile North Pole Exploration Rover (VIPER) mission. The rover was to be sent to the moon’s south polar region aboard a commercial lander called Griffin from Astrobotic Technology, and was to explore terrain including permanently shadowed regions to better understand the extent and shape of water ice there.

In a briefing announcing the cancellation, agency officials said VIPER costs had increased by more than 30 percent, prompting the agency to review the project’s termination. NASA had confirmed VIPER would launch in 2021 at a cost of $433.5 million. The latest estimate was $609.6 million, with a launch scheduled for September 2025, said Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

“In this case, the remaining projected expenses for the VIPER program would have either canceled or disrupted several other missions in our commercial lunar payload services pipeline,” said Nikki Fox, NASA’s associate administrator for science. “So, we made the decision to abandon this particular mission.”

VIPER has suffered from a series of supply chain issues that have delayed the delivery of unspecified key components dating back to the pandemic, Kearns said. “Delays have happened over and over again for a number of key components,” he said, with small incremental delays that were harder for the mission to plan for than one major delay.

This complicated the process of building the vehicle, which he described as being about the size of a small car built from the inside out. “A lot of the components that were delayed were actually in the interior of VIPER, so as components were delayed, it started to force the VIPER team to delay assembly, to delay integration, to delay initial testing.”

The spacecraft is now complete in development, but environmental testing is only just beginning. The revised cost and timeline assume the spacecraft will pass environmental testing without any problems, Kearns said. “I will tell you that environmental testing at the system level of spacecraft development generally reveals problems that need to be corrected, which will take more time and money,” he said.

Canceling VIPER now would save NASA at least $84 million, he said. That amount could grow if VIPER’s launch is pushed back beyond November 2025, which would require waiting nine to 12 months for suitable lighting conditions to return at the polar landing site.

Much of the science that VIPER could have done will be done by other missions, including landers and orbiters, Kearns and Fox said. However, the mobility that VIPER could have provided may not be available until NASA’s Lunar Terrain Vehicle, a rover intended for the crewed Artemis missions but also remotely controlled, is delivered later this decade.

NASA plans to disassemble the VIPER spacecraft to reuse its hardware and other components. But first, NASA will consider proposals from U.S. companies and international partners to launch the VIPER spacecraft on its own at no cost to the government. Proposals are due to arrive at NASA on Aug. 1.

Griffin’s Mission Review

Aside from its own development problems, VIPER has been hit by delays from Griffin, the Astrobotic lander that is scheduled to deliver the vehicle to the moon under a $322 million CLPS mission order. NASA said Griffin is now expected to be mission-ready no later than September 2025.

With the VIPER program canceled, NASA will keep the Griffin mission. Instead, the mission will become a technology demonstration, carrying a mass simulator instead of a rover to test Griffin’s ability to land large payloads.

NASA considered sending scientific payloads instead, Kearns said, but since the lander is designed to carry a spacecraft, it lacked the payload equipment and capabilities such as power and communications that such a payload would need.

“We believe that if we asked Astrobotic to make changes like this, it would push their timeline further back,” he said of potential payload adjustments. “It would increase the cost to the government. It would delay a successful demonstration of a landing at the South Pole by the large Griffin lander, which we very much want to see.”

Astrobotic will also be free to launch its own commercial payloads. Astrobotic CEO John Thornton said in an interview that the company is considering launching a test of its LunaGrid power generation service aboard Griffin. “We want to fly fast but we also want the mission to be more impactful than just the landing itself,” he said.

The Griffin spacecraft without the Viper would land at the moon’s south polar region, though it wouldn’t necessarily land at the same location NASA chose for the Viper spacecraft, he said. That would depend on any new payloads the spacecraft registers for the vehicle, with the option to go to a safer landing site to reduce the risk to the mission.

Kearns and Thornton said the agency notified the company of the decision recently, but declined to elaborate. One industry source said NASA informed Astrobotic of the decision just a day before it was publicly announced.

“This has certainly been a turbulent and challenging year for Astrobotic,” he said, referring to the January launch of its first lunar lander, Peregrine, which suffered a fuel leak after launch and was unable to attempt a landing on the moon. The cancellation of the VIPER mission “is another kick in the gut, but we’ll deal with it,” he added.

Kearns said NASA believes Griffin will be able to land safely on the moon, with or without Viper on board, noting NASA-funded work for the company to conduct additional tests of the propulsion system. “We trust them to go out and attempt this landing, or we wouldn’t be continuing to work with them.”

“I’m always an optimist. You have to be in the space industry,” Thornton said. “I’m excited about what we can turn this into.”

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin