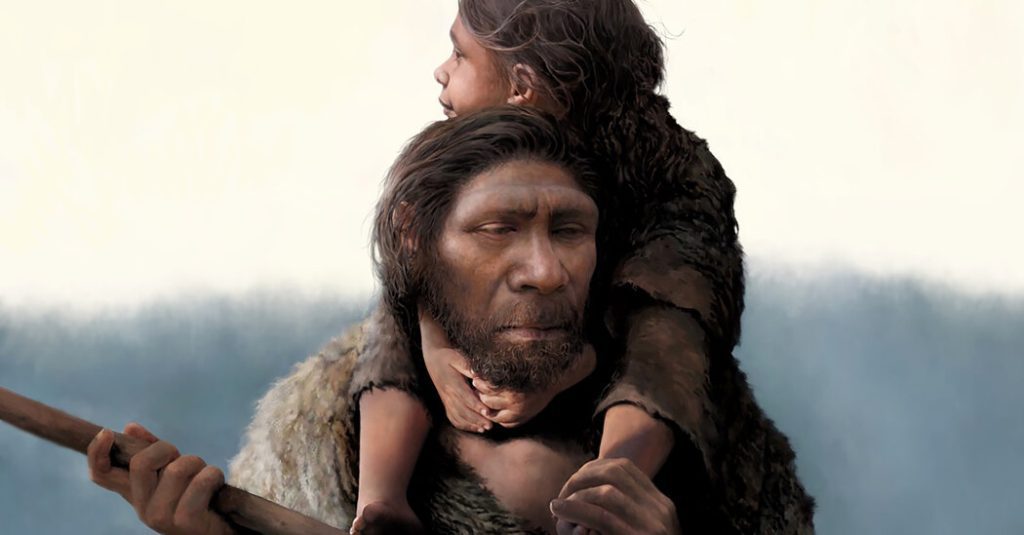

Analyzing fossils from a cave in Russia, scientists found the first known Neanderthal family: a father and teenage daughter and others who may have been close cousins.

the findings, Published Wednesday in Nature, painted a tragic picture of our extinct relatives, who roamed Eurasia tens of thousands of years ago. Scientists said the family, part of a group of 11 Neanderthals found together in the cave, likely died together, possibly from starvation.

The study was conducted by a team of researchers that included Svante Pääbo, a Swedish geneticist who for 25 years had been revealing the secrets of Neanderthals, by extracting his DNA from Cave floor dirt to repeat brain cells. Earlier this month, he won a Nobel Prize for his efforts.

said Dr. Babu, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. “It was an amazing trip.”

For his first study of Neanderthal DNA in 1997, Dr. Pääbo and his colleagues dug into a skull cap discovered in 1856 in a German quarry. Over the next few years, they collected more DNA from other museum specimens, gathering hints about Neanderthal evolution and their relationships with living humans. In the end, Dr. Pääbo and his collaborators dug up enough ancient DNA to reconstruct The entire genome of Neanderthals.

The new discovery came from a Siberian cave called Chagyrskaya. Paleoanthropologists with the Russian Academy of Sciences began digging there in 2007, discovering parts of Neanderthal bones and teeth. Researchers also found 90,000 stone tools in the cave, along with butchered bison bones.

The cave may have served as a seasonal home for Neanderthals. Perhaps they came to Chagyrskaya to hunt bison, which migrate every year to graze in the nearby grasslands.

In 2020, Dr. Pääbo and colleagues presented published First DNA discoveries from Chagyrskaya: a complete genome collected from a Neanderthal woman’s finger bone. Her genes showed she was closer to Neanderthals more than 3,000 miles away in Croatia than those 65 miles away in another cave known as Denisova.

This kinship indicates that Neanderthals in Siberia did not belong to a single population. They expanded eastward from Europe at least twice – first to Denisova, and then after tens of thousands of years to Chgerskaya.

Dr. Pääbo’s team has continued testing other Neanderthal fossils from the cave. They infected a genetic maternal complex, and ended up with DNA from 11 individuals: six adults and five children. The fossils – along with stone tools and bison bones – settled in the same layer of sediment in the cave.

“Archaeologists call this a ‘short career,’” said Laurits Skov, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who was a co-author of the new study. In other words, all the bones were trapped in this layer of dirt over a relatively short period of time, from Geologically, “But the word ‘short’ here means two thousand years or less.”

However, Dr. Skov believes that 11 Neanderthals all lived around the same time. This is because many of them were close relatives.

To search for kinship among Neanderthals, Dr. Skov and his colleagues scanned the fossil’s DNA for small differences. Two of the fossils shared enough differences that they were first-degree relatives. One came from a broken paragraph that appears to belong to an adult male. The other came from an age that seemed to come from a teenage female. If these estimated ages are accurate, the samples may have come from siblings or from a father and daughter.

DNA from the fossils allowed the researchers to more accurately determine the relationship. Scientists have taken advantage of the fact that mothers pass on an extra set of genes to their children, called Mitochondrial DNA. The Chagyrskaya guy and the girl had different mitochondrial DNA, which rules out a sibling relationship.

“This means we can prove that this was in fact a father and a daughter,” Dr. Skov said.

Other excavations have provided hints of other family relationships. The father proved to be close to two other adult males in Chagyrskaya. An adult woman and a boy also shared enough DNA that they are likely related to each other.

Dr. Skov said that Neanderthals were related to the fact that they all died at once. “It seemed to be one event in which they all died,” Dr. Skov said. If they died at different times, it would mean that the group had returned to the same cave over many years to bury each member – a scenario that Dr. Skov considers highly unlikely.

Researchers have found other evidence that Neanderthals died in large numbers. In 2010, a team of researchers in Spain mentioned Dozens of Neanderthals died about 49,000 years ago when the roof of a cave collapsed on them.

Dr. Skov said that there was no sign of such a disaster in Chrysostom. It was speculated that the band’s bison hunts failed for a year, resulting in starvation.

None of the eleven Neanderthals in Chgerskaya showed any genetic link to Neanderthals in Denisova Cave. But Dr. Skov and his colleagues discovered a connection to a third cave nearby known as Okladnikov. Two Neanderthal fossils found in Okladnikov have genetic links with Chygerskaya. Dr. Skov and his colleagues combined 13 Neanderthals from the two caves to create the genetic profile of their entire population.

In one analysis, they compared the genetic diversity of males and females. The researchers found that the Y chromosomes shared by males were somewhat similar. On the other hand, the mitochondrial DNA passed down from mothers to their babies was very diverse.

This pattern appears in many people Communities Men tend to stay in the group they were born into and women often move into new groups before childbearing. Dr. Skov and his colleagues concluded that among Neanderthals, women moved from one band to the next.

“We estimate that 60 to 100 percent of women in any community actually come from other communities,” said Dr. Skov.

Dr. Skov and his colleagues then added the genetic diversity in Neanderthals to obtain clues about their population size. Larger populations tend to have more genetic diversity.

“Looking at these particular patterns of diversity that we see in the data, we can see that there isn’t a lot of it,” Dr. Skov said.

This lack of diversity likely means that Siberian Neanderthals lived in small groups of 20 or fewer people. This also means that the total population of Neanderthals in Siberia was very low – perhaps less than a thousand. “They are similar to those of mountain gorillas, which are an endangered species,” said Dr. Skov.

Lara Cassidy, a geneticist at Trinity College Dublin who was not involved in the study, cautioned that the work may only reveal the social structure of Neanderthals who lived on the eastern edge of their group.

She noted that harsh Siberian winters may have kept their numbers lower than elsewhere. Obtaining DNA from groups of Neanderthals in the Middle East or Europe could reveal a clearer picture of how they lived across the entire range.

“There will be more to come, so this is a milestone,” she said.

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin