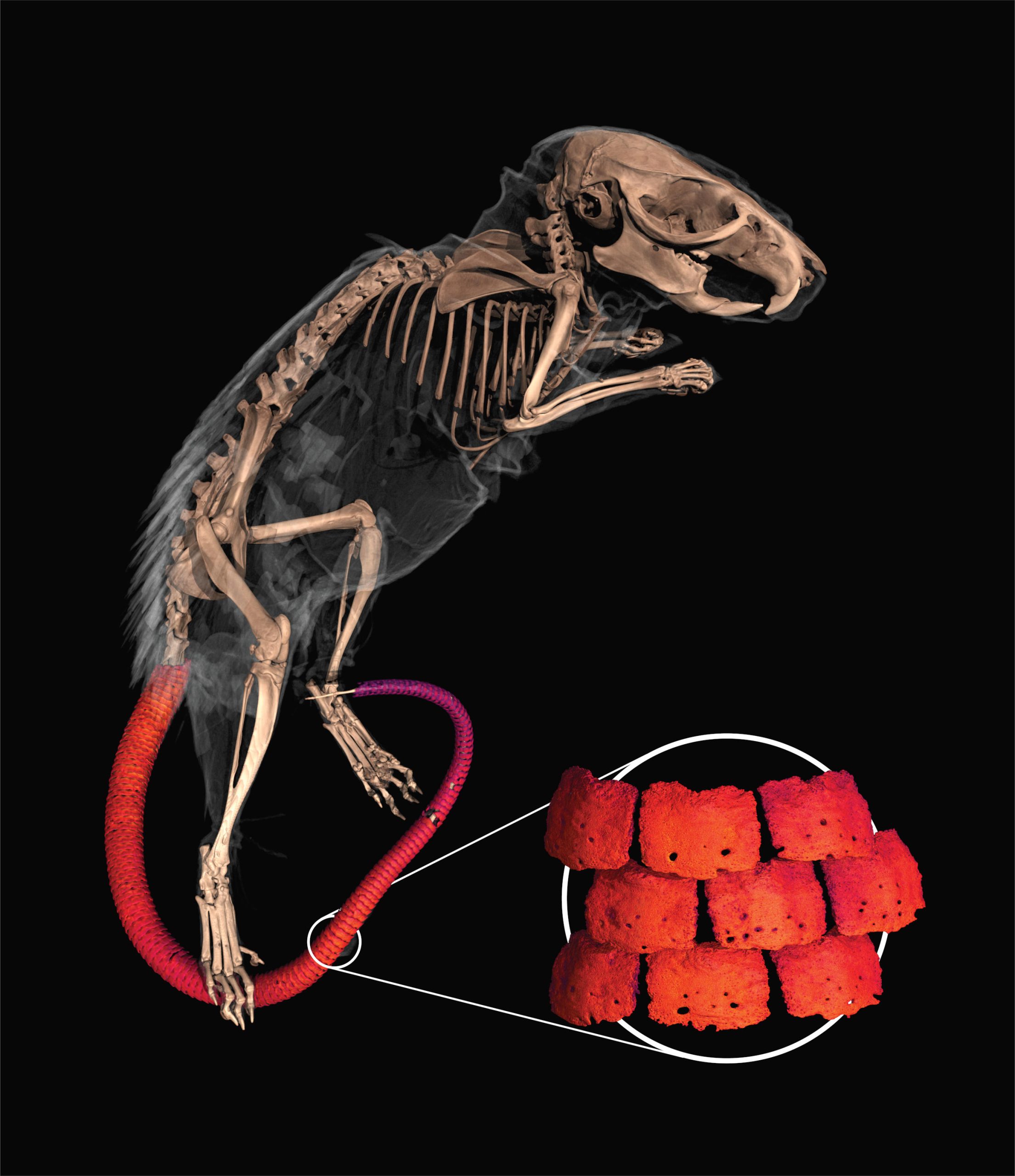

Spiny mice produce bony plates called osteoderms under the skin of their tails, which detach when the animal is attacked, giving it a quick getaway. Credit: Edward Stanley

Unlike crocodiles, turtles, lizards, dinosaurs and fish, which possess bony plates and scales, mammals have long replaced the carapace of their ancestors with an insulating layer of hair.

Armadillos, which have a defensive, succulent shell of overlapping bones, are thought to be the only living anomaly. However, a new study was published in the journal iScience It is unexpectedly shown that African spiny mice generate similar structures under the skin of their tail, which have been largely undiscovered so far.

The discovery was made during a routine CT scan of museum specimens for OpenVertebrate, an initiative to provide 3D models of vertebrate organisms to researchers, educators, and artists.

“I was scanning a mouse specimen from the Yale Peabody Museum, and their tails looked abnormally dark,” said co-author Edward Stanley, director of the Digital Imaging Lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Suppose at first that the discoloration is caused by a defect introduced during sample preservation. But when he analyzed the X-rays several days later, Stanley noticed an unmistakable feature he was familiar with.

“My entire PhD focused on the development of ostoderm in lizards. Once the sample scans had been processed, the tail was clearly covered in osteoderms.”

Bony spiny rats have been observed at least once before and were noted by German biologist Jochen Niethammer, who compared their architecture to medieval stonework in an article. Published in 1975. Niethammer correctly interpreted the plates as a type of bone but never followed up on his initial observations, and the group was largely ignored for decades—until scientists discovered another peculiarity apparently unrelated to spiny mice.

a Study from 2012 This proven spiny rat can completely regenerate injured tissue without scarring, an ability common in reptiles and invertebrates But it was not previously known in mammals. Their skin is also particularly fragile, tearing with nearly a quarter of the force required to injure the skin of an ordinary mouse. But spiny mice can heal twice as fast as their close relatives.

The researchers, hoping to find a model for human tissue regeneration, set out to map the genetic pathways that give spiny mice their extraordinary healing abilities. One of these researchers, Malcolm Madden, happened to have a lab in the building across from Stanley’s office.

“Spiny mice can regenerate skin, muscles, nerves, spinal cord and possibly even heart tissue, so we keep a colony of these rare creatures for research,” said Madden, a professor of biology at the University of California. University of Florida The lead author on the study.

Madden and colleagues analyzed the development of osteoderms of spiny mice, confirming that they are in fact similar to those of armadillos but most likely evolved independently. Osteoderma is also different from the scales of pangolins or the feathers of hedgehogs and porcupines, which are composed of keratin, the same tissue that hair, skin, and nails are made of.

There are four genera of spiny mice, which all belong to the subfamily Deomyinae. However, apart from the similarities in DNA And perhaps the shape of their teeth, scientists have not been able to find a single feature they have in common classify It is this group that distinguishes it from other rodents.

Suspecting that their differences might only be profound, Stanley surveyed additional museum specimens from all four races. In all of them, the spiny tails of mice were found to be covered by the same bony sheath. Deomyinae’s closest relatives — the gerbils — lacked osteoderms, meaning the trait had only evolved once, in the ancestor of the earlier divergent spiny mice.

The ubiquitous presence of osteoderms in the group indicates that they perform an important protective function. But what that function might be wasn’t immediately clear, given another curious characteristic of spiny mice: Their tails are uncharacteristically detachable. Tail loss is so common in some species of spiny rat that approximately half of the individuals of a given group lack it in the wild.

“That was a real head-scratcher,” said Stanley. Spiny rats are notorious for being able to remove their tails, which means the outer layer of skin peels off, leaving behind muscle and bone. Individuals often chew off the remainder of the tail when this happens.”

Despite its ability to regenerate, wagging the tail is a trick that spiny rats can only perform once. Unlike some lizards, they cannot regrow their tails, and not every part of the tail detaches easily.

To find out why rodents that seem ambivalent about keeping their tails have trouble covering them with armor, the authors turned to a group of gecko-tale fish from Madagascar. Most geckos lack bony skin, but as their name suggests, fish-tale geckos are covered in thin, overlapping plates, and, like spiny mice, have incredibly fragile skin that flakes off at the slightest provocation.

According to Stanley, the osteoderms in gecko-tale fish and spiny mice likely acted as a kind of escape mechanism.

“If a predator bites on its tail, the shield may prevent the teeth from sinking into the tissues underneath, which do not separate,” he said. The outer skin and its complement of bony coating retracts away from the tail when attacked, allowing the mouse a quick escape.

Reference: “Osteosteoclasts in the Spiny Mouse Mammal Acomys and the Independent Evolution of the Skin Shield” By Malcolm Madden, Trey Polvador, Aroud Polanco, W. Brad Barbazok, and Edward Stanley, May 24, 2023, Available Here. iScience.

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106779

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin