Ed Law wants to save Earth from deadly asteroids.

Or at least, if there’s a big space rock coming our way, Dr. Lu, a former NASA astronaut with a Ph.D. in applied physics, wants to find it before it hits us — hopefully with years of forewarning and opportunity for humanity. to spend it.

On Tuesday, the B612 Foundation, a nonprofit group that Dr. Lu helped found, announced the discovery of more than 100 asteroids. (The institution’s name is a reference to Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s children’s book, “The Little Prince”; B612 is the character’s main asteroid.)

This in itself is not noticeable. New asteroids are being reported all the time by sky watchers around the world. This includes hobbyists with backyard telescopes and robotic surveys that systematically survey the night sky.

Remarkably, B612 did not build a new telescope or even make new observations with existing telescopes. Instead, B612-funded researchers applied sophisticated computational capabilities to years-old images — 412,000 of them in the Digital Archives at the National Infrared Optical Astronomy Research Laboratory, or NOIRLab — to sift the asteroids out of 68 billion points of cosmic light. captured in the pictures.

This is the modern method of astronomy” Dr. Lu said.

Search adds to “Planetary Defense” Efforts by NASA and Other Organizations around the world.

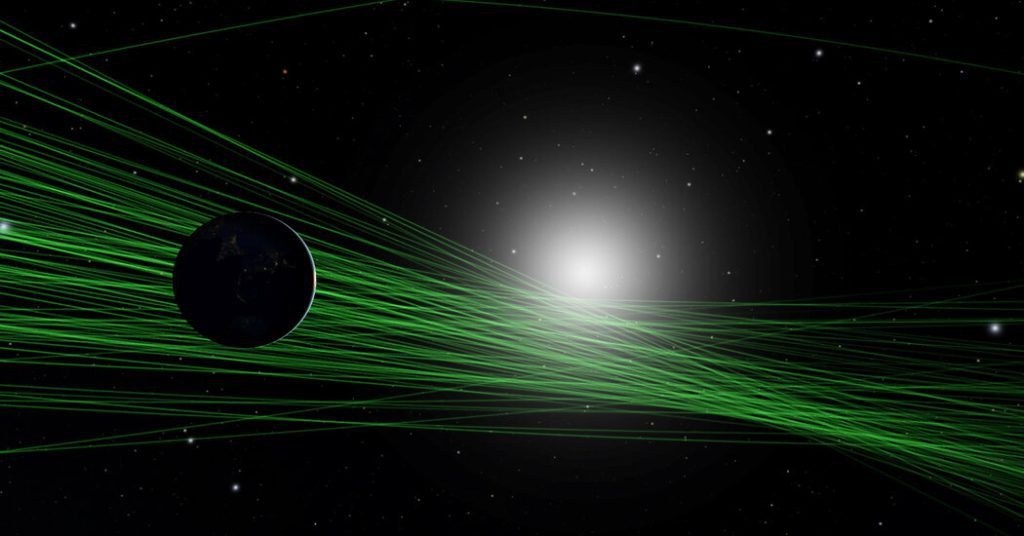

Today, of the 25,000 asteroids near Earth that are at least 460 feet in diameter, only about 40 percent have been found. The remaining 60 percent—about 15,000 space rocks, each with the potential to release energy equivalent to hundreds of millions of tons of TNT in a collision with Earth—remains undiscovered.

B612 collaborated with Joachim Moeyens, a graduate student at the University of Washington, and doctoral advisor, Mario Juric, professor of astronomy. They and colleagues at the university’s Institute for Data-Intensive Research in Astrophysics and Cosmology have developed an algorithm capable of examining astronomical images not only to determine which points of light might be asteroids, but also to see which points of light in images taken different nights are actually the same asteroid.

Essentially, the researchers developed a way to detect what was actually seen but not observed.

Usually, asteroids are discovered when the same part of the sky is photographed multiple times during a single night. A patch of the night sky contains many points of light. The distant stars and galaxies remain in the same order. But objects much closer, within the solar system, move quickly, and their positions change over the course of the night.

Astronomers call a series of observations of a single moving object during one night a “tracking.” The tracker provides an indication of the object’s movement, guiding astronomers to where they might be looking for another night. They can also search for old photos of the same object.

Many astronomical observations that are not part of systematic asteroid searches inevitably record asteroids, but only at a single time and place, not the multiple observations needed to piece together the small paths.

The NOIRLab images, for example, were taken primarily by the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope in Chile as part of a survey of nearly one-eighth of the night sky to map the distribution of galaxies in the universe.

The extra spots of light were ignored, because they weren’t what astronomers were studying. “It’s just random data in just random pictures of the sky,” Dr. Lu said.

But for Mr. Moeyens and Dr. Juric, a single point of light that isn’t a star or galaxy is a starting point for their algorithm, which they called Tracklet-less Heliocentric Orbit Recovery, or THOR.

The law of gravity controls the motion of the asteroid. THOR creates a test orbit corresponding to the observed point of light, assuming a certain distance and velocity. Then it calculates where the asteroid was on the subsequent and previous nights. If a point of light appears there in the data, it could be the same asteroid. If the algorithm can string five or six observations together within a few weeks, that’s a promising candidate for discovering an asteroid.

In principle, there are an infinite number of possible test orbits to examine, but this requires never being impractical to calculate. In practice, since asteroids cluster around certain orbits, the algorithm only needs to consider a few thousand carefully selected possibilities.

However, calculating thousands of test orbits for thousands of potential asteroids is a daunting task to crack the numbers. But the advent of cloud computing – the massive computing power and data storage distributed over the Internet – makes this possible. Google contributed time on its Google Cloud platform to this effort.

“It’s one of the coolest apps I’ve seen,” said Scott Benberthy, Director of Applied Artificial Intelligence at Google.

So far, scientists have examined about one-eighth of the data for one month, September 2013, from the NOIRLab archives. THOR has produced 1,354 potential asteroids. Several of them were already in the asteroid catalog maintained by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center. Some of them have been observed previously, but during only one night and the small path was not enough to confidently determine an orbit.

The Minor Planet Center has confirmed that 104 objects are new discoveries so far. The NOIRLab archive contains seven years of data, indicating that there are tens of thousands of asteroids waiting to be found.

“I think it’s coolAnd thesaid Matthew Payne, director of the Minor Planet Center, who was not involved in developing THOR. “I think it is very interesting and also allows us to make good use of the archival data that already exists. “

The algorithm is currently configured to only find main belt asteroids, those with orbits between Mars and Jupiter, and not near-Earth asteroids, those that could collide with our planet. Recognizing near-Earth asteroids is more difficult because they are moving faster. Different observations of the same asteroid can be separated in time and distance, and the algorithm needs to do more number-crunching to make the connections.

“It will certainly succeed,” said Mr. Moen. “There’s no reason why it wouldn’t. I really haven’t had a chance to try it out.”

THOR not only has the ability to discover new asteroids in old data, but it can alter future observations as well. Take, for example, Vera C Robin Observatoryformerly known as the Large Universal Survey Telescope, is currently under construction in Chile.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the Rubin Observatory is an 8.4-meter telescope that frequently scans the night sky to track changes over time.

Part of the observatory’s mission is to study the large-scale structure of the universe and identify distant supernovae, also known as supernovae. Closer to home, you will also discover a large number of objects smaller than one planet orbiting the solar system.

Several years ago, some scientists suggested that the Rubin Telescope’s observational patterns could be modified so that it could locate more asteroid impacts and thus locate more dangerous yet undiscovered asteroids more quickly. But this change would have slowed down other astronomical research.

If the THOR algorithm proves to work well with Rubin’s data, the telescope would not need to scan the same part of the sky twice per night, allowing it to cover twice the area instead.

“This could in principle be revolutionary, or at least very important,” said Zeljko Ivezic, telescope director and author of a scientific paper describing THOR and testing it against observations.

If the telescope can return to the same place in the sky every two nights instead of every four nights, it could benefit other research, including the search for supernovae.

“This would be another effect of the algorithm that has nothing to do with asteroids,” Dr. Evezek said. “It shows very well how the landscape is changing. The science ecosystem is changing because now software can do things that you wouldn’t even have dreamed of 20 or 30 years ago that you didn’t even think of.”. “

For Dr. Lu, THOR offers a different way to achieve the same goals he had a decade ago.

At the time, B612 was eyeing an ambitious and much more expensive project. The non-profit organization was to build, launch and operate its own space telescope called Sentinel.

At the time, Dr. Lu and the other leaders of B612 were frustrated by the slow pace of the search for dangerous space rocks. In 2005, Congress mandated NASA to locate and track 90 percent of near-Earth asteroids 460 feet or more in diameter by 2020. But lawmakers didn’t provide the money NASA needed to get the job done, and the deadline passed with less than half being found. those asteroids.

Raising $450 million from private donors to subscribe to Sentinel was challenging for B612, especially since NASA was considering building its own space telescope to detect asteroids.

When the National Science Foundation gave the go-ahead for the Rubin Observatory, B612 re-evaluated its plans. “We can quickly turn around and say, ‘What is the different approach to solving the problem that we are there to solve?'” Dr. Lu said. “

The Rubin Observatory is scheduled to make its first test observations in about a year and be operational in about two years. Dr. Evcic said ten years of Rubin’s observations, combined with other searches for asteroids, could meet Congress’ 90 percent goal.

NASA is accelerating planetary defense efforts, too. Its asteroid telescope, called the NEO Surveyor, is in the initial design phase, and aims to launch in 2026.

Later this year, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission will launch a projectile at a small asteroid and measure how much the asteroid’s path has changed. China’s National Space Agency is working on a similar mission.

For B612, rather than squabbling over a telescope project costing nearly half a billion dollars, it could contribute to less expensive research efforts like THOR. Last week, it announced that it had received $1.3 million in gifts to fund further work on cloud computing tools for asteroid science. The foundation has also received a grant from Tito’s Handmade Vodka that will match up to $1 million from other donors.

B612 and Dr. Lu are now not just trying to save the world. “We answer a trivial question about how vodka relates to asteroids.” He said.

More Stories

Boeing May Not Be Able to Operate Starliner Before Space Station Is Destroyed

Prehistoric sea cow eaten by crocodile and shark, fossils say

UNC student to become youngest woman to cross space on Blue Origin