CNN

–

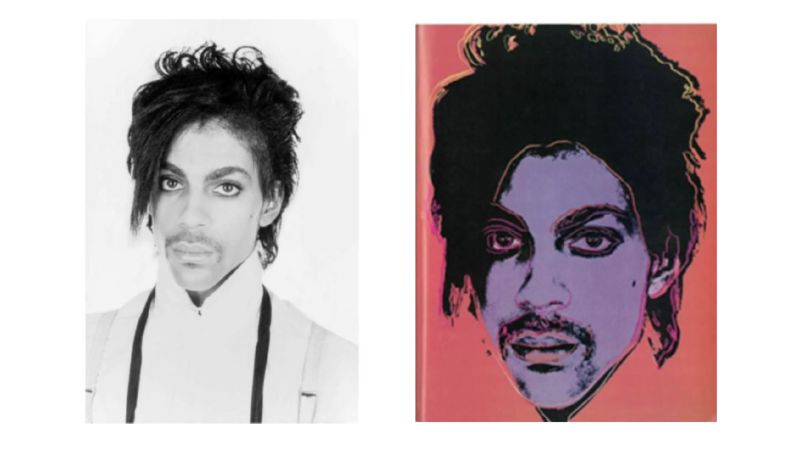

The Supreme court Wednesday will consider whether the late Andy Warhol infringed the photographer’s copyright when he created a series of silkscreens for the Prince of Music.

The case represents a rare court foray into the world of visual arts and has drawn the attention of those in the art world who say the Court of Appeals decision against Warhol calls into question the legitimacy of generations of artists who have been inspired by their pre-existing works. .

Museums, galleries, collectors, and experts have also considered asking judges to balance copyright law with the First Amendment in a way that protects artistic freedom.

At the center of the case is the so-called “fair use” doctrine in copyright law that allows unauthorized use of copyrighted works in certain circumstances.

In the case at hand, a district court ruled in Warhol’s favour, basing its decision on the fact that the two works in question had a different meaning and message. But the appeals court overturned – ruling that the new meaning or the new message was not sufficient to qualify for fair use.

Now the Supreme Court must come up with the appropriate test.

“Fair Use protects the First Amendment rights of both speakers and listeners by ensuring that those whose speech includes dialogue with pre-existing copyrighted work are not prevented from sharing that speech with the world,” said a group of art law professors who support the Andy Warhol Foundation. Judges in court papers.

Lawyers for the Warhol Foundation maintain that the artist created the “Prince Series” – a group of paintings that altered a pre-existing image of the musical prince – in order to comment on “celebrity and consumerism”.

They said that in 1984, after Prince became a star, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create a portrait of the prince for an article called “Violet Fame.”

At the time, Vanity Fair licensed a black and white photo taken by Lynne Goldsmith in 1981 when Prince was not well known. Warhol was to use Goldsmith’s picture as an artist reference.

Goldsmith, who specializes in celebrity photos and makes money from licensing, initially took the photo while on assignment with Newsweek. Her photos of Mick Jagger, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, and Bob Marley are all part of the court record.

Vanity Fair published the illustration based on her photo — once a full page and once a quarter page — with attribution to it. She wasn’t aware that Warhol was the artist her work would be reference to, but she got paid $400 in licensing fees. The license stipulates that “No other use rights are granted.”

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol went on to create an additional 15 works based on her image. At some point after Warhol’s death in 1987, the Warhol Foundation acquired the copyright rights to the so-called “Prince Series”.

Fans pay tribute to Prince

In 2016, after Prince’s death, Conde Nast, the parent company of Vanity Fair, published an homage using one of Warhol’s Prince Series work on the cover. Goldsmith has not been given any credit or credit for the image. She did not receive any wages.

Upon learning of the series, Goldsmith acknowledged her work and contacted the Warhol Foundation to report the copyright infringement. Her photo is registered with the United States Copyright Office.

The Warhol Foundation – believing Goldsmith would sue – sought a “declaration of non-infringement” from the courts. Goldsmith challenged the copyright infringement claim.

A district court ruled in favor of the Warhol Foundation, concluding that use of the image without permission and without fees constituted fair use.

The court said Warhol’s work was “transformative” because it conveyed a different message from Goldsmith’s original work. She opined that the Prince series “can reasonably be seen as transforming Prince from a frail and uncomfortable character into a larger-than-life avatar”.

The 2nd Circuit of the US Court of Appeals However, he reversed this and said that use of the images does not necessarily fall within fair use.

The appeals court said the district court was wrong to assume the “art critic role” and base its fair use test on the meaning of the artwork. Instead, the court should have considered the degree of visual similarity between the two works.

Under this criterion, the court said, the Prince Series was not transformative, but instead “consistently resembles” the Goldsmith image and is therefore not protected by fair use.

It based its judgment on the fact that a secondary work, even if it added a “new expression” to the source material, could be excluded from fair use. The Court of Appeal said that the secondary work’s use of the original source work must have an artistic purpose that is “completely different and new” and artistic in nature “so that the secondary work is separate from the raw materials used to create it”. The court asserted that the primary work should not be barely recognizable in the secondary work, but at least it should “include something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work”.

The court said the “overall purpose and function” of the Goldsmith portrait and Warhol’s prints are identical because they are “portraits of the same person”.

The court concluded that “The Prince Series decisively retains the essential elements of Goldsmith’s image without significantly adding or altering these elements.”

In appealing the case on behalf of the Warhol Foundation, attorney Roman Martinez argued that the appellate court had erred badly by preventing courts from considering the meaning of the work as part of a fair use analysis.

He warned the court that if it were to adopt the logic of the appeals court, it would overturn established copyright principles and lull creativity and expression “at the heart of the First Amendment.”

According to Martinez, copyright law is designed to promote innovation, sometimes building on the achievements of others.

Martinez emphasized that the fair use doctrine – “which dates back to at least the nineteenth century” – reflects the recognition that strict enforcement of copyright law would “stifle the very creativity that laws are designed to foster”.

He noted that Warhol’s work is currently in collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Smithsonian and Tate Modern in London. From 2004 through 2014, Warhol’s auction sales exceeded $3 billion.

Martinez said Warhol made substantial changes by cropping and resizing Goldsmith’s image and changing the angle of Prince’s face while changing the tones, lighting, and details.

Martinez argued, “While Goldsmith portrayed Prince as a weak human being, Warhol made major alterations that erased humanity from the image, as a way of commenting on society’s conception of celebrities as products, not as people,” he added. ”

Goldsmith’s attorney, Lisa Platt, told the judges an entirely different story.

“For all creators, the Copyright Act 1976 makes a long-standing promise: to create innovative works, and copyright law guarantees your right to control whether, when and how your work is shown, distributed, reproduced or adapted,” she wrote.

She said the multi-billion dollar creators and licensing industries “rely on this premise.”

She said the Andy Warhol Foundation should have paid Goldsmith’s copyright fees. Platt argued that Warhol’s work was nearly identical to that of Goldsmith.

“Fame is not a ticket to trampling on the copyrights of other artists,” she said.

The Biden administration supports Goldsmith in the case.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prilugar, for example, noted that book-to-film adaptations often introduce new meanings or messages, “but this has not been seen as a sufficient justification independently for unauthorized copying.” She said Goldsmith’s ability to license her image and earn fees was “undermined” by the Warhol Foundation.

The Art Institute of Chicago and other museums told the court that the appeals court’s decision caused uncertainty not only for the works of art themselves, but also the market for copies of works the museum creates through catalogs, documentaries and websites.

Smokey Robinson on Prince: He was a genius

Museum lawyers also noted that the lower court’s opinion “failed to take into account” the old artistic tradition of using elements from pre-existing works in new works and asked the Supreme Court to reconsider the appeals court’s ruling.

In the Baroque era, for example, Giovanni Panini painted Modern Rome (pictured in court papers) depicting an exhibition displaying famous art. It includes copies of pre-existing works including the Statue of Moses by Michelangelo, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Order of Constantine, David, Apollo, and Daphne, and its fountains in Piazza Navona. Museums have argued that contemporary artists continue to make use of pre-existing artwork. For example, street artist Banksy painted a painting, “Girl with a Pierced Drum,” on a building in Bristol. It was in reference to Johannes Vermeer’s masterpiece, “The Girl with a Pearl Earring” from 1665.

The museums argued that “all of these works would not be considered transformative under the Second Circle approach”.

More Stories

Heather Graham Opens Up About Being Separated From Her Parents For 30 Years

Heather Graham hasn’t spoken to her ‘estranged’ parents after they warned her Hollywood is ‘evil’

‘Austin Powers’ star Heather Graham’s father warns Hollywood will ‘take my soul’